- Home

- Fresh Produce Knowledge

- Produce Supply Chain

The Fresh Produce Supply Chain

Introductory Comments

The Fresh Produce Supply Chain has been at the centre of my professional and academic engagement since 1987, in one form or other. That year I joined the buying department of what was then New Zealand's most innovative supermarket company, Foodtown. I had two stints in the business. 1987-1992 and 1996 -1998. What I did during those years, what the focus was in the 1993 -1995 period, will all flow into this website, because what ever I did involved learning. And learning generates knowledge.

What I will share on these pages are some key elements that formed part of my supply chain thinking thirty years ago. These are contained in a "time capsule" called my Doctoral thesis.

I make reference to what I was thinking about all those years ago, because the generation of knowledge is a life long journey, and one typically ignores the past at one's peril.

This is not just applicably to the Produce Supply Chain but is a universal truth - albeit that the focus here is most certainly on fresh produce.

Every piece of academic research at Masters or Doctoral level is informed through a comprehensive literature review that aims to

- understand what is already known about the topic one wants to research;

- identify possible gaps in the existing literature;

- motivate the learner/student in their pursuit of robust research that will make a contribution to the body of knowledge, just like those have done who came before.

Where my thinking was significantly influenced by the work of others, this will be acknowledged through an external link.

Supply Chain Management

"Supply chain management evolved as a discipline during the late 1980s as managers started to apply just-in-time principles and quick response principles to distribution processes (Fearne,1994). In his study of the UK's progress in introducing quick response processes, Fearne also comments on supply partnership issues. He expresses the view that the practice of suppliers and supermarket retailers working closely together, in order to achieve supply chain optimisation, was lagging significantly behind the rhetoric about partnershipping. Breaking down attitudes and prejudices from the past are, according to Fearne, elementary to creating the more open approach necessary, in order to secure common benefits for supply chain partners. Fearne suggests that the catalyst for closer partnering will be the experiencing of diminishing returns for both supplier and retailer."

Maurer, J. 1999. Improving the (New Zealand) Fresh Produce Supply Chain.

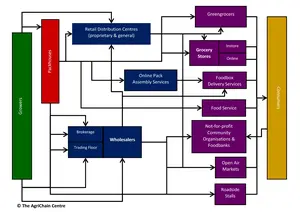

The Produce Supply Chain

Fearne was generalising in the observations I attributed to him in my research all those years ago. Much of his work at the time though was associated with the Tesco initiative to develop the original version of Dunnhumby, together with the University of Kent, where Fearne taught at the time, as part of the team around Professor David Hughes. The entire team was fairly heavily focused on the produce supply chain, as the supermarket industry had started to understand the strategic importance of the produce department within the store range, which went well beyond the produce department's share of store sales.

Both Andrew Fearne and David Hughes are still around and active within the wider food value chain arena.

In my thesis, I discussed some of the emotional flashpoints that can flare up between grower/shippers and retailers when they are working directly with each other, rather than with the help of a wholesale market or a broker. One of these flashpoints then was related to transport.

"Improving the produce supply chain through achieving improved transport solutions can not occur in a sustainable way over night. It requires cooperation between retailers and their suppliers and most likely also a level of co-opetition between suppliers. This will be difficult to achieve if retailers focus on opportunistic tactical purchasing decisions. These come at the expense of deteriorating relationships with key grower/shippers."

"There is a supplier reaction to the notion of a retailer collecting its own produce that could at best be described as consistently negative. Discussing improvements through changes in transport arrangements translates for many supplier into 'letting the retailer directly determine how my business is being run'. Suppliers find it instinctively more acceptable when the retailers' determination is exercised through conventional and precedential behaviour, e.g., tough price and terms negotiations, rather than through an attempt at 'open book' supply or value chain construction."

"It will therefor be necessary to find ways to defuse the emotional powder keg that is part and parcel of supplier mind sets, when integrated transport solutions or similar activities are raised. However, it has to be acknowledged that a large proportion of supplier anxiety in this space is perfectly justified.

Maurer, J. 1999. Improving the (New Zealand) Fresh Produce Supply Chain.

And Today?

Well, those were my views then. Today, 30 years later in round figures, my views have not changed. Have supply chain participants been able to defuse the 'emotional powder keg' I referred to in my thesis? Let it put me this way: There have been some earnest attempts to defuse the keg, but the job is not done yet. The keg is still there, the fuse is still in place, and the jury is out on whether the earnest attempts under way, will evolve into lasting solutions to everyone's satisfaction.