- Home

- Fresh Produce Knowledge

- Produce Supply Chain

- Fresh Produce Supply Chain Structure

Fresh Produce Supply Chain Structure

Overview - Fresh Produce Supply Chain Structure

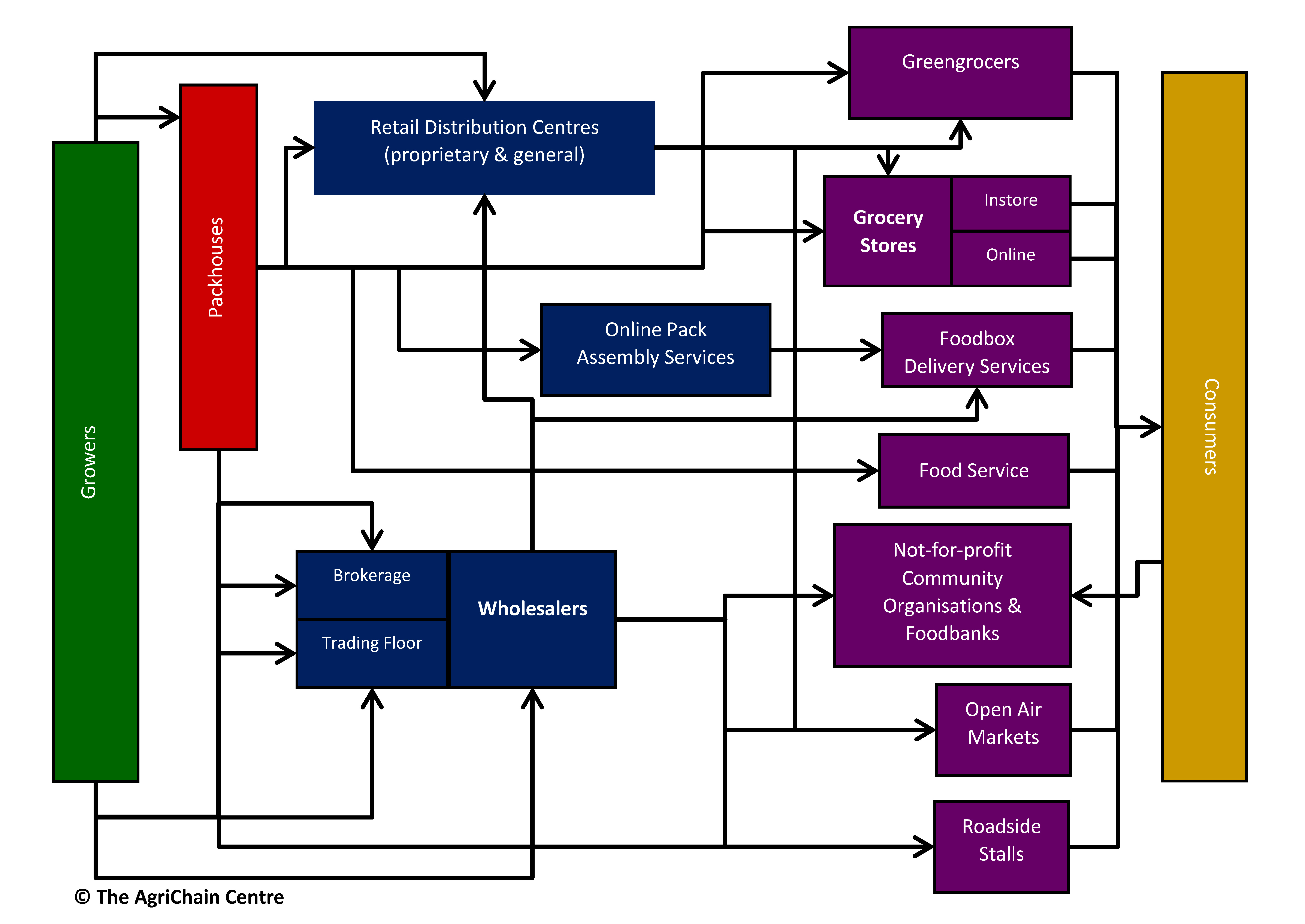

This diagram is a high level illustration of the New Zealand domestic fresh produce supply chain structure. The pathways of export crops leaving the country and import crops entering New Zealand are not shown in this version of the diagram. The building blocks and pathways, and the way they are structured here in this country's domestic fresh produce supply chain, are, in the main, those that can also be found in the other OECD economies and elsewhere.

Throughout the Fresh Produce Systems Knowledge website, this diagram contributes to the structure and the way information and knowledge is being shared. But please appreciate that this diagram is multi-layered. Each of the representative building blocks shown stands for a multitude of real life commercial or NGO entities, varying in scope from a car boot seller in the 'Roadside Stalls' category, to a dominant local wholesaler operating as a coo-operative and a corporate retailer owned by offshore principals.

Production & Post-harvest Structure

Within the the fresh produce supply chain structure, growers are organised with a singular upon focus. That is to successfully growing a crop from planting to harvest - and earning enough money to support their growing operations, their families and achieving sufficient surplus to allow for ongoing investment into the business.

This means the typical grower likes nothing better than for someone to come along and either buy everything that has been grown and take it away there and then, or to organise storage if some of the crop and/or the sales patterns require or allow that. The kiwifruit industry has organised this well. The industry is segmented into growers, cool store operators and packers, and onshore supply managers. Some overlap exists but not every grower gets to be a cool store operator and many growers would not want to have a bar of it.

How this plays out in reality is entirely dependent on the type of produce being grown, the structure of the particular supply chain, or even supply chains, a grower is part of, market conditions (more about that elsewhere) and, inevitably, the prevailing weather conditions during the crops' growing and harvest periods.

Fresh Produce Supply Chain Structure - Retail

The closer fruits and vegetables get to the consumer within the retail segment of the fresh produce supply chain structure, the more structured the process becomes that the produce is subjected to.

It starts with grade and size expectations communicated by retail customers or their agents. There is a limit to how many kilos or items of produce that are acceptable per crate or carton. Carton or crate type and size are typically also specified, or if not, growers are likely to get hit with a re-packing charge should this become necessary, depending on which retail supply chain their produce is required to enter.

Each crate or carton needs to carry an identifying label that states content, grower name and quantity as a minimum. In many cases additional information is sought. If produce turns up at a market floor or retail distribution centre without identification, there is a reasonable expectation for that produce to be sent back to where it came from.

Produce is not dispatched from farms anymore just because a grower has harvested and feels the urge to get some of his crop off the property. Nothing much happens without an order, or, at the very least, a call to a market floor a day or two before to discuss the possibility of supplying if no regular arrangements exist. Growing, without a clear understanding of who the next value chain partner is, can be a risky business. Produce prices are relatively unstructured and fluctuate based on supply and demand and catching the low side of the price curve can be a very painful exercise.

Retail Distribution Centres typically have on-site quality control staff and any produce accepted must pass a quality check beforehand. Product that fails to pass is either rejected or buyers will attempt to re-negotiate the price. In the worst-case scenario, the produce will turn up again at the grower’s farm gate.

Produce that makes it onto a market floor or into a distribution centre can typically be expected to be ship out again to the final retail destination within 12-18 hours. This tends to occur as part of a composite delivery of produce where individual optimum produce temperature zones are ignored. So, if a produce item such as apples, had come from a controlled atmosphere cool store where regulated temperatures were the norm, all these rules go out the window at the latest when the apples get sent to stores.

It goes without saying that produce reaching a retail outlet is expected to remain in pristine condition in the rear store until the produce manager deems it necessary to move it onto the retail shelves. There it needs to maintain its condition for as long as it takes a customer to purchase the produce, take it home and hopefully use it before it deteriorates to the extent that a customer complaint is received, as deteriorate it will.